Red Bull Investing: Why The Riskiest Stocks Have Been Vastly Outperforming Safe Ones

Introduction

Let’s say you believed that the higher the risk, the higher the reward. Let’s say you loved taking risks. Let’s say you participated in all the Red Bull–sponsored extreme sporting events you could, and you watched those you couldn’t participate in. And you drank their sodas like water, regardless of any health risks.

What kinds of stocks would you buy?

I like to break down factors into seven categories: value, growth, stability, quality, sentiment, momentum, and size. A Red Bull investor would look for the following in a stock:

- Value. Extremely underpriced or extremely overpriced stocks. Those are definitely the riskiest.

- Growth. Stocks whose growth is high but far from certain. Again, definitely the riskiest.

- Stability. The most unstable stocks possible.

- Quality. Low-quality stocks. No question there.

- Sentiment. Stocks with huge changes in sentiment; stocks which investors can’t make up their minds about; stocks that are either flying under the radar or are heavily shorted.

- Momentum. Total mean reversion! Stocks with negative momentum. Beaten-down stocks that are barely hanging on.

- Size. Tiny stocks, low-priced stocks.

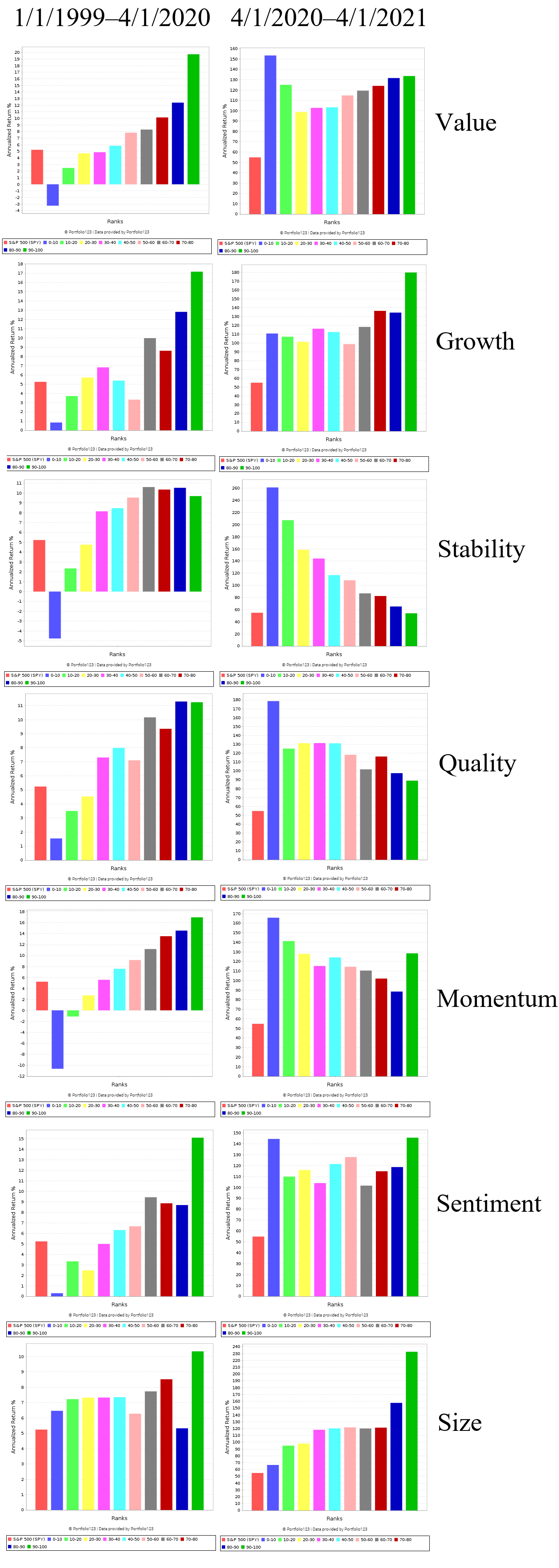

Well, check out the following charts:

The left-hand charts are for these factors between January 1999 and April Fools’, 2020, a few days after the market hit bottom. The right-hand charts are for the most recent four quarters, 4/1/2020 to 4/1/2021. Let’s focus on the right-hand charts for a moment.

- Value. As you can see, the most expensive stocks have gone up the most, but besides that, there’s been a steady favoring of cheap stocks as well. The fairly-priced stocks have done the worst.

- Growth. These factors have been relatively unaffected. Growth stocks still rule supreme.

- Stability. The most unstable stocks have outperformed like mad.

- Quality. Low quality is highly favored.

- Momentum. Stocks with terrible (or downward) momentum have done by far the best; stocks with high momentum have done OK, but only at the very top end of the chart.

- Sentiment. Stocks that are undergoing major changes in sentiment, whether higher or lower, are doing the best.

- Size. The tiniest stocks are crushing the others.

We are at a unique moment in history, folks: a moment when the riskiest stocks have the highest return.

Chart Methodology

For those of you interested in how I came up with these charts, here’s my method. If not, feel free to skip this section.

I created these seven factor groups and tested them using Portfolio123. Each of them consists of five factors (see illustration below), equally weighted (except for the size group, which has only three factors). The charts reflect the annualized returns if you were to take all stocks listed on major US exchanges with prices over $1 and divide them into deciles according to how they rank on an equally weighted multi-factor ranking system made up of those five factors, with reconstitution every four weeks. I chose the five factors in each on a discretionary basis—they’re mostly relatively common factors that I use myself. The data I used was FactSet’s.

[table id=red-bull_investing /]

The seven ranking systems I created for testing are all public. If you subscribe to Portfolio123, go to Advanced Research Search. In the Author box put “yuvaltaylor” and in the Ranking System Name box put “factors.”

How Could This Happen?

Some assessments of the impact that the Robinhood and wallstreetbets Reddit crowd have had on the market conclude that it’s pretty low. After all, the amount of money these investors have is absolutely dwarfed by the holdings of institutional investors.

But in the stock market, prices are driven not by how much money is invested, but by how many shares are being bought and sold. A $5 billion large-cap fund with 100 holdings that replaces a quarter of its holdings quarterly is going to have less impact on market prices than a $5 million small-cap investor with 20 holdings who replaces a quarter of her holdings daily.

How is that possible?

Scholars agree that market impact is roughly proportional to the square root of the ratio of the volume of shares the investor is trading to the total daily volume. So let’s call a unit of market impact MI. A typical small cap stock will have a daily dollar volume of $5 million while a typical large cap stock will have a daily dollar volume of $100 million. The $5 billion large-cap fund will make 100 trades a year of $50 million apiece. Each one will have a market impact of the square root of 0.5, or 0.71, for a total market impact of about 71 MI. The small-cap fund will make 1,000 trades a year of $250,000 apiece. Each one will have a market impact of the square root of 0.05, or 0.224, for a total market impact of 224 MI. So this hypothetical small investor with $5 million will have three times more impact on stock prices than the large-cap investor with $5 billion.

Michael Batnick recently published a good piece on this, from which I borrow the information that follows. According to the Financial Times, individual investors are now trading almost 25% of total volume, nearly as much as hedge funds and mutual funds combined (the bulk of trading continues to be done by high-frequency market makers). If we assume that they are trading in smaller stocks than hedge funds and mutual funds, they will have a much larger impact on prices. A recent paper looked at Robinhood traders alone, and estimated that despite having a market share of 0.2% in the second quarter of 2020, they accounted for 10% of the cross-sectional variation in stock returns. And then consider that the ratio of retail traders to institutional traders has grown significantly since then. There was, of course, a craze in “meme stock” trading that peaked on January 29, 2021, and retail trading has declined about 60% since then. But I don’t wish to prognosticate about what will happen over the next few quarters. All I want to say is that the ball game has changed.

The Theory and Psychology of Risk

The conventional explanation as to why people invest in risky things like stocks is that they believe that the higher the risk, the greater the reward. If this weren’t true, the argument goes, everybody would invest in bonds. And certainly nobody would invest in such incredibly risky assets as cryptocurrency and the stock of nearly bankrupt companies if it weren’t for the belief that they could make themselves rich by doing so.

A case in point is Peter L. Bernstein’s Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk, widely considered the standard book on the subject. His perspective is the conventional one: “nobody takes a risk in the expectation that it will fail.” The only reason people take risks is because they have confidence that they can succeed. That confidence, of course, can be misplaced. But without it, no risks can be taken.

Or take Marc Gerstein’s cogent explanation of risk in capital markets:

In order to induce (bribe, if you will) anybody to invest in an asset that has any risk, you must offer an expectation that the return will be above the risk-free rate. There is no guarantee that any outcome will be successful, but you must be able to justify a before-the-fact expectation of a “premium” above the risk-free rate.

From “Marc Gerstein Explains Risk”

This standard argument is the foundation of risk-based economic theory. It underlies the Capital Asset Pricing Model, which is completely premised on the belief that expectations of risk correlate to expectations of reward. If the risk of a bet going wrong is certain financial death, then the expectation of reward has to be immense.

But this is simply not how people operate. Risk has its own psychological rewards that are completely unrelated to financial success or failure.

Red Bull is the poster child for this. Their entire marketing campaign is built around risk-taking for no good reason. The wallstreetbets followers are no different. Many of the GME buyers took the attitude that if they lost money, so what? It was fun being in on the gamble. There are no rewards for no-parachute skydiving or bungee-cord jumping. Go to Bolivia and talk to the folks who take mountain bikes down the death road. They’ll tell you: it’s the risk itself that is its own reward. If it weren’t the world’s most dangerous road, the number of folks who take it down would shrink radically.

And this attitude isn’t just limited to adolescent males. Look at the roster of Red Bull athletes. You’ll find old and young, men and women, fat people and thin people, rich and poor. Risk is fun for everyone.

What does this mean for the risk-reward relationship?

I’ve written about this at length before but, to oversimplify, in financial terms it looks like this:

With no risk, there’s no financial reward. As risk increases, financial reward increases, up to a certain point. After that point, risk becomes its own reward, a psychological reward, and financial reward decreases. And with the riskiest bets, you’re more likely to lose money than to gain any.

To maximize reward, you need to find that sweet spot between not enough and too much risk.

Conclusion

Prior to the pandemic, the conventional wisdom was to put all your money in index funds because there was no way you could beat the market. Now the conventional wisdom is that stockpicking is fun and profitable. Prior to the pandemic, the conventional wisdom was to minimize your losses by making safe bets. Now the conventional wisdom is you only live once, so go ahead and gamble.

We’ve seen how this has affected the factors I use to trade stocks. I believe that those factors will continue to work, at least for small caps and microcaps, and at least for a few more years. The behavior we’ve seen in the last four quarters is extreme, and soon some sort of equilibrium between the old behavior and the new will be reached.

But until that happens, all bets are off—except, perhaps, the riskiest ones.

The entire time frame over which your strategy was tested was characterized (dominated) by increasing liquidity (capital) being poured into the financial markets, reflected n declining interest rates. As we all know, as supply of anything rises, the lower the quality of the buyers that are able to obtain same.

What evidence do you have to suggest that your conclusions will continue to prevail in a new regime, in which the supply of liquidity holds constant (reflected in no meaningful movement one way or another in interest rates) or is contracted (meaning rising rates)?

None at all. I will not speculate about whether or not the “Red Bull Investing” phenomena will characterize any future period. (In fact, I would rather not speculate about future periods at all.) So far, the second quarter of 2021 looks nothing like the previous four quarters. Red Bull investing had a fascinating year-long run, and it was a phenomenon that provides evidence for my thesis that investors sometimes take risks that have nothing to do with expected returns. But you’re 100% right about the liquidity being poured into the financial markets, and that’s something I probably should have mentioned in my article.