Alphanomics: The Study of Security Mispricing

I just finished reading Alphanomics by Charles M. C. Lee and Eric So, published by a small academic press in 2015. The subtitle is The Informational Underpinnings of Market Efficiency, but that doesn’t really give a sense of the book, which essentially summarizes the last five decades of academic research into market pricing mechanisms. I’d like to give readers a summary of what the book accomplishes.

I: Is the Market Efficient?

There are a lot of arguments against the efficient market hypothesis (the belief that the price of a stock reflects all available information and therefore approximates the intrinsic value of a company), and Lee and So seem to marshal practically every one of them. But my favorite is their surfing analogy.

Market efficiency, or so argue its proponents, is “an inevitable outcome of continuous arbitrage,” where arbitrage is defined as “trading aimed at profiting from imperfections in the current price.” Because so much arbitrage is going on, prices rapidly adjust to reflect the information available.

Lee and So point out that this belief “is akin to believing that the ocean is flat, simply because we have observed the forces of gravity at work on a glass of water. No one questions the effect of gravity, or the fact that water is always seeking its own level. But it is a stretch to infer from this observation that oceans should look like millponds on a still summer night. . . . If we are in the business of training surfers, does it make sense to begin by assuming that waves, in theory, do not exist? A more measured, and more descriptive, statement is that the ocean is constantly trying to become flat.”

Because price discovery is an ongoing process, there is always going to be a lot of adjustment as the market searches for some sort of equilibrium, and this adjustment involves lots of mispricing and correction of that mispricing even as new information and signals come in. “In fact,” Lee and So write, “it strikes us as self-evident that arbitrage cannot exist without some amount of mispricing. Therefore, either both mispricing and arbitrage exist in equilibrium, or neither will.” (What Lee and So mean by “mispricing” is essentially the divergence between the market price and the net present value of a security.)

Lee and So then take on the idea that abnormal returns (pricing anomalies) are a compensation for risk factors. This doesn’t fit with empirical observations. There is a great deal of evidence that “healthier and safer firms, as measured by various measures of risk or fundamentals, often earn higher subsequent returns. Firms with lower beta, lower volatility, lower distress risk, lower leverage, and superior measures of profitability and growth, all earn higher returns.” In other words, these companies all appear to be less risky than comparable companies.

Let’s take the opposite assumption (please note that Lee and So don’t go here) for a moment. Let’s hypothesize that the market is fundamentally inefficient and that while arbitrage makes it slightly more efficient, it doesn’t even begin to make it fully efficient. Let’s hypothesize that mispricing is ever-present in part because information is always imperfect. Let’s hypothesize that arbitrage – an industry that costs, in management fees, $600 billion per year, as Lee and So estimate – succeeds only occasionally and is mostly making stabs in the dark. Under this model, investing in less risky assets is more likely to succeed than investing in highly risky assets, and there’s no need to worry about “compensation for risk factors.”

II: Who Are “Noise Traders”?

In 1984, Robert J. Shiller came up with the idea that you can classify investors into two types, smart-money investors and ordinary investors. Fischer Black quickly characterized these ordinary investors as “noise traders.” These are basically people who do not trade on the basis of information about fundamentals; they ignore arbitrage methods and instead trade on the basis of other beliefs, fads, or impulses. If noise traders are more predominant than smart-money investors, you end up with a model that can explain asset pricing very well. It can explain why the price of most stocks is far more volatile than the stock’s intrinsic value could possibly be, why closed-end funds veer so far from their net asset values, why the same stock can trade in two different markets with wide differences in price, and why investor inflows and outflows are inversely correlated with subsequent returns. (The efficient market hypothesis can explain none of these “anomalies.”) With the burgeoning field of behavioral economics, we can understand better the various psychological forces that influence stock pricing, and we can recognize that successful arbitrage can be based not just on the disparity between a stock’s price and its intrinsic value, but on the patterns of (mis)behavior that shape that disparity. However, as Lee and So conclude, “In a noisy market, we are all noise traders.”

III: Why Does Value Investing Still Work?

Lee and So ask the big question: why hasn’t the value effect been arbitraged away? Why has it persisted for so long?

The answer isn’t that value stocks are riskier. If you incorporate quality (or growth potential, which is really the same thing) into your definition of value, as Benjamin Graham did and Lee and So do, value stocks are actually less risky than expensive/growth stocks.

The answer is behavioral. Ordinary investors prefer glamor stocks, stocks with exciting stories; value stocks are pretty boring. Ordinary investors look at recent price performance of a stock and think it will persist; value stocks are usually low-priced. Ordinary investors overweight far-future earnings and underweight present earnings due to overconfidence when information is highly uncertain; wise value investors concentrate on known/present revenue, earnings, and cash flow when judging a stock’s worth.

IV: The Practical Limits of Arbitrage

“Information complexity matters,” write Lee and So. Financial markets have a hard time quickly processing information about stocks, and when subtle signals arise (for example, between the lines of quarterly earnings reports or among “boring” or low-volume stocks that are not subject to much attention), they tend to be ignored for a while, resulting in persistent mispricing.

Another limitation is due to whether the information is right or not. Let’s say you identify a large discrepancy between the market price of an asset and its estimated value. As Lee and So write, “there are two possibilities. The first is that the market price is wrong and the discrepancy represents a trading opportunity. The second is that the theoretical value is wrong and the discrepancy is due to a mistake in the valuation method. How can an active investor tell the difference?” Arbitrage is limited by this kind of doubt.

In addition, capital constraints come in many forms. One is high transaction costs, which tend to minimize trading, which in turn tend to diminish arbitrage. Another is that near market tops, when money can be put to little good use, come the heaviest cash inflows. But around market bottoms, outflows tend to congregate and funding constraints are severe, and that is precisely when money can be put to best use.

With all these limits to effective arbitrage, it’s no wonder that securities are so often mispriced. As Lee and So sum it up, “smart money seeking to conduct rational informational arbitrage faces many costs and challenges. These challenges can dramatically limit the deployment of arbitrage capital in financial markets, leading to significant price dislocations. Such effects are pervasive across asset groups.”

V: How Can We Tell If Excess Returns Are a Result of Increased Risk-Taking or Market Mispricing?

If you’re a smart investor, you’d want to capitalize on market mispricing and avoid risk-taking as much as possible. But academics and professional investors have come to opposite conclusions about the source of excess returns. Warren Buffett and his myriad followers talk about “margins of safety” and espouse value investing as far safer than any other kind. At the same time, a number of Nobel Prize–winning economists say that the excess returns from value investing, like those from momentum investing and other factor-based investing (including even low-volatility investing!), are based on compensation for additional risk-taking. One couldn’t come up with more opposed conclusions.

The orthodox position among academics has been that an asset’s expected returns are determined by its sensitivity to a given “risk factor,” as measured by a linear asset-pricing model. But as Lee and So point out, referring to a large number of more recent academic studies, these models fail to distinguish between mispricing and risk; many of the “risk factors” do not conform to any common-sense ideas of what is actually risky; the models can’t explain post-earnings announcement drift or the fact that firms with strong accounting fundamentals outperform firms with weak ones; looking at the returns of the various “risk factors” on their own predicts future returns better than their factor-loading (sensitivity) on the factor portfolio; and the regression-based model is based on the assumption that the returns of a given firm are uncorrelated over time (independently and identically distributed), a violation of which leads to an over-rejection of the null hypothesis. In other words, there’s no good reason to use the complicated linear multi-factor asset-pricing model that so many use these days.

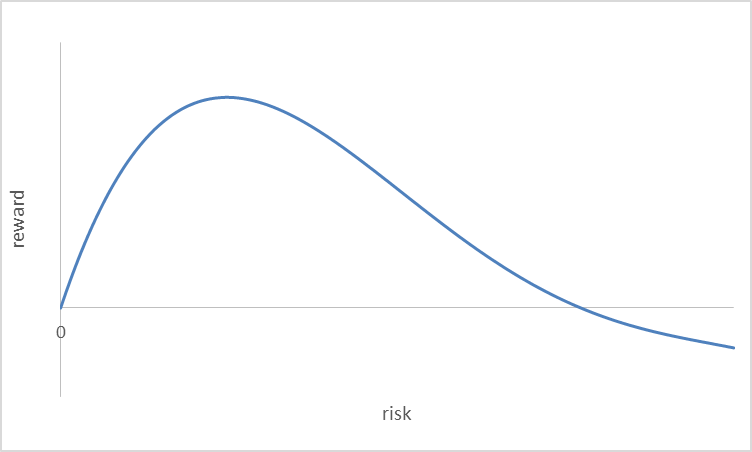

What Lee and So do not challenge is the idea that there is a linear relationship between risk and reward. As I have shown, the relationship is by no means linear; past a certain point, the riskier the asset, the lower the reward, and the relationship is therefore best characterized by a curve whose shape looks something like this:

VI: Conclusion

It’s hard not to come away from this book with mixed feelings about academic research on investing. On the one hand, highly questionable conclusions have become orthodoxy, and the basic models taught to students have very little, if any, empirical foundations. On the other hand, academics are challenging these models, and their research has been excellent and very useful.

The book, I think, should be an essential read for anyone who wants to understand how current asset-pricing models work (or don’t). But I think the authors don’t go quite far enough.

My own conclusion after reading Alphanomics is that markets are fundamentally inefficient, that arbitrage is mostly ineffective, and that mispricing is seldom risk-related. There are plenty of very good behavioral reasons for investors to be more attracted to risky investments than to safe ones, thus presenting plenty of opportunities for investors who take advantage of the consequent mispricing of safer securities.

And, practically speaking, how do you do that?

The first step is to find mispriced safe securities. Take all the factors that academics have shown work – in Lee and So’s words, quoted above, “lower beta, lower volatility, lower distress risk, lower leverage, and superior measures of profitability and growth” – and combine them with value factors, which, as Buffett and other value investors have shown, create a margin of safety. Use a powerful screen or, better yet, a ranking system such as those available from Portfolio123 (design your own, or rely on the seven pre-built “core” ranking systems).

The next step is to wisely invest in safe securities and sell them when and only when they begin to seem unsafe. (Or, conversely, short those securities that are the riskiest.)

The great investors have long recognized that you can get superior returns at the same time as minimizing your risk. An inefficient market is ripe for successful arbitrage, and it’s up to smart investors to take advantage of that.

2 Replies to “Alphanomics: The Study of Security Mispricing”